Corneal scarring is a significant cause of visual impairment and blindness globally, particularly in developing countries. It results from a variety of causes, including infections, injuries, surgical complications, and diseases that affect the cornea, the clear front surface of the eye.

Corneal infections, such as bacterial, fungal, or viral keratitis, are prominent causes of corneal scarring. These infections can lead to inflammation and damage to the corneal tissue, resulting in scarring that obscures vision. Injuries or trauma to the eye, including chemical burns or physical abrasions, can also cause corneal scarring.

Additionally, surgical procedures on the eye, while often necessary to correct other vision issues, can sometimes lead to scarring as a complication. Diseases that affect the cornea, such as keratoconus or dry eye syndrome, can further contribute to the development of corneal scarring.

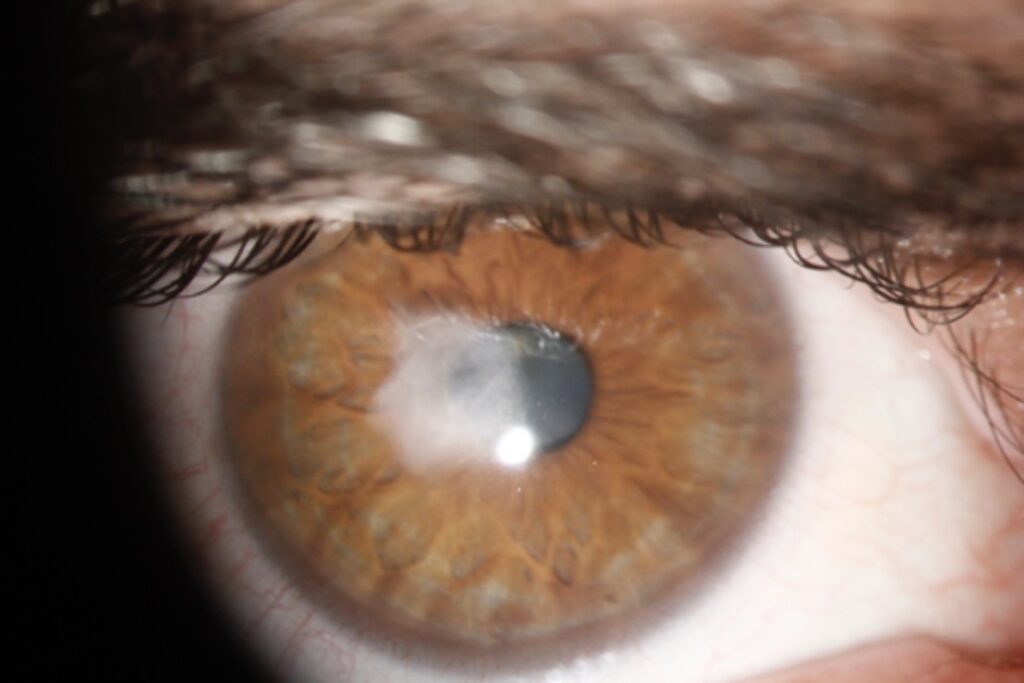

The impact of corneal scarring on vision can range from mild to severe, depending on the extent and location of the scar tissue. Scarring that affects the central vision area of the cornea can significantly impair visual acuity, leading to blurred vision or even blindness.

Traditional treatments for corneal scarring have included the use of corrective eyewear, such as glasses or soft contact lenses, to improve visual acuity. However, these methods often provide limited improvement for those with significant scarring. More invasive treatments, such as corneal transplantation, have been used to replace the scarred corneal tissue with healthy donor tissue. While effective, corneal transplants carry risks of complications and require long-term management [1][2].

Introduction to Scleral Contact Lenses (SCL)

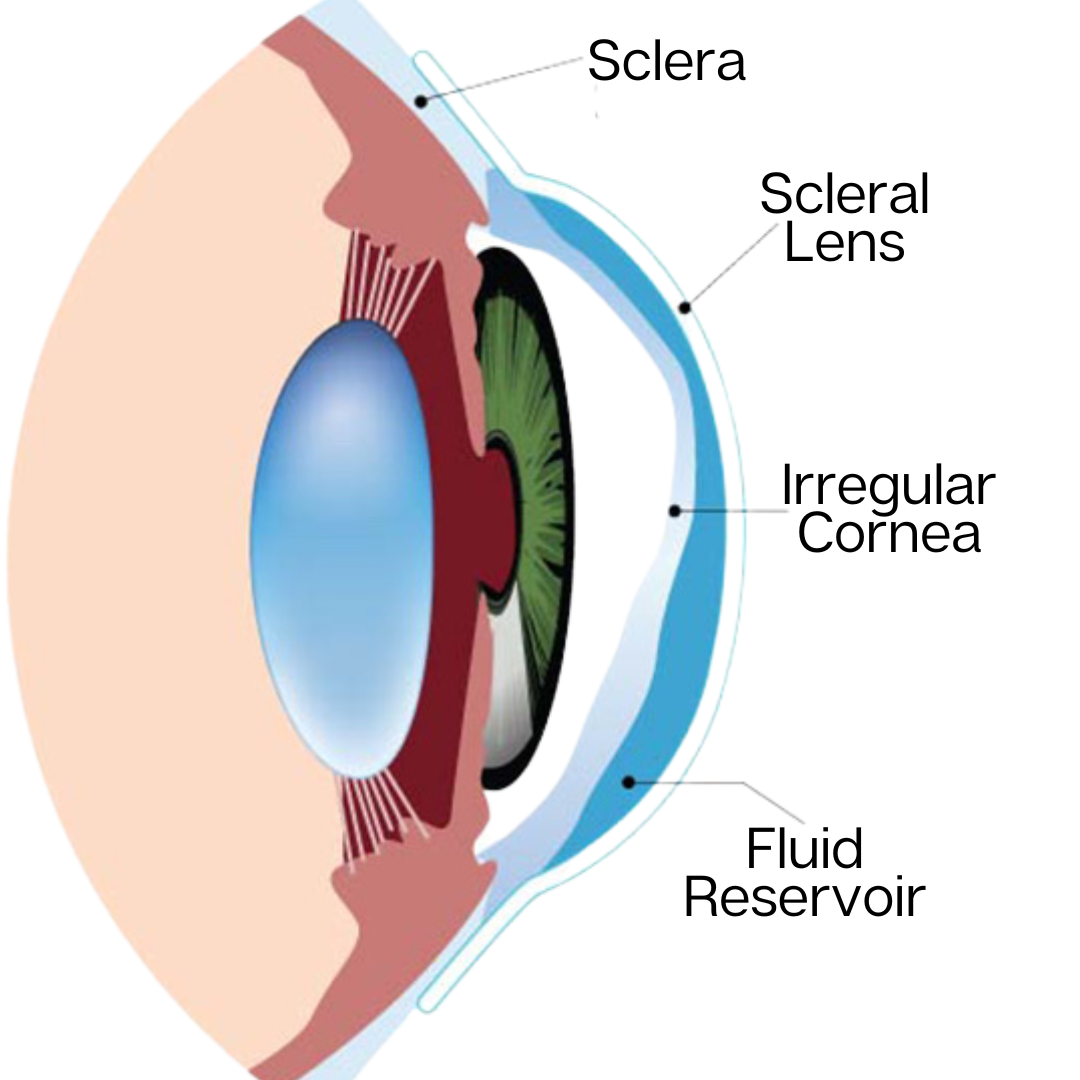

Scleral contact lenses (SCL) represent an innovative, non-invasive option for managing corneal scarring and improving vision. Unlike traditional contact lenses that rest directly on the cornea, scleral lenses vault over the cornea and rest on the sclera, the white part of the eye. This design allows for a tear-filled space between the lens and the cornea, which can help to smooth out irregularities caused by scarring and provide a clearer optical surface.

Scleral lenses differ from corneal contact lenses as they cover the entire cornea and provide a cushion of tears that can help maintain corneal hydration, making them an ideal solution for individuals with corneal scarring resulting from conditions like keratoconus, where the cornea becomes thin and cone-shaped, leading to irregular astigmatism and myopia [1]. Scleral lenses typically offer more comfort and better visual outcomes than regular contact lenses, as they create a smoother surface over irregular corneas.

The use of scleral lenses has been shown to improve visual acuity and comfort for patients with moderate to severe keratoconus, offering a safe and effective alternative to more invasive procedures. These lenses combine the optical quality of rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses with the comfort of soft lenses, making them a preferred option for many patients. Additionally, scleral lenses can provide therapeutic benefits by protecting the cornea from further damage and maintaining a hydrated ocular surface, which is crucial for individuals with dry eye syndrome or those who have experienced corneal trauma [1].

Scleral lens wear is also beneficial for scleral lens patients who find traditional eyewear or soft contact lenses insufficient for their needs. Scleral lenses provide a non-surgical way to manage corneal scarring and can be custom-fitted based on each individual’s unique prescription needs.

In summary, wearing scleral lenses offers a promising non-invasive solution for managing corneal scarring and improving vision in patients with a variety of corneal conditions. Their ability to provide both visual and therapeutic benefits makes them an important tool in the arsenal of options for treating corneal scarring.

Understanding Corneal Scarring

What is Corneal Scarring and Its Impact on Vision

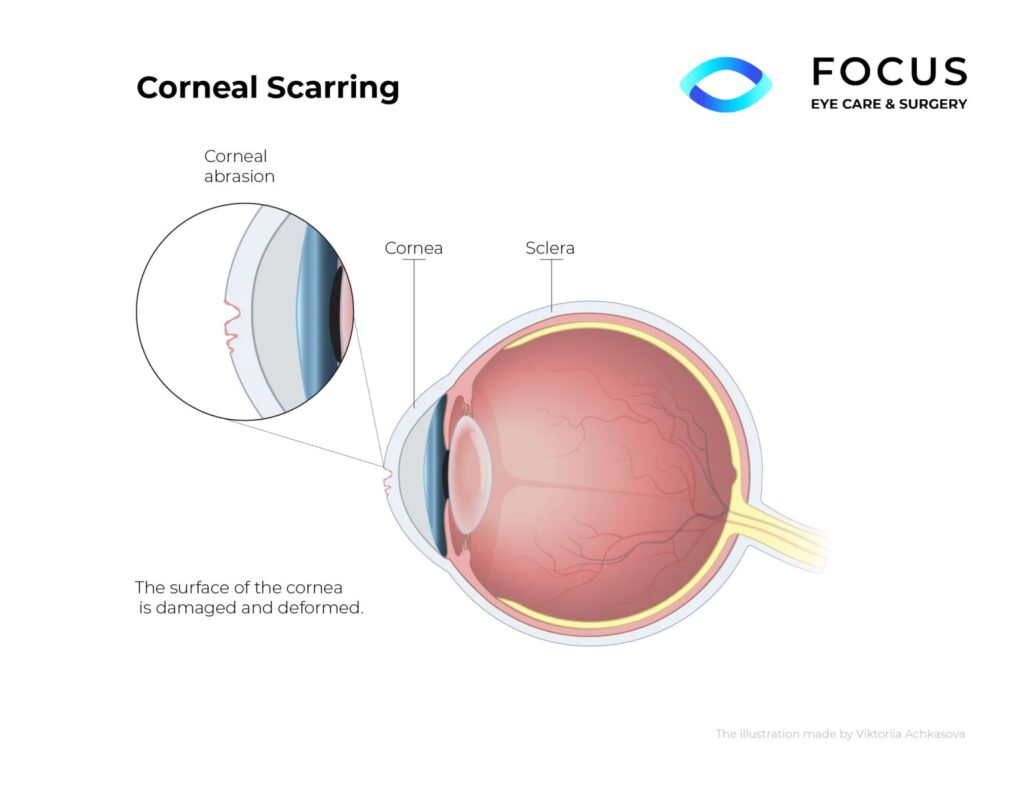

Image from: https://www.qeilaser.com.au/corneal-scarring

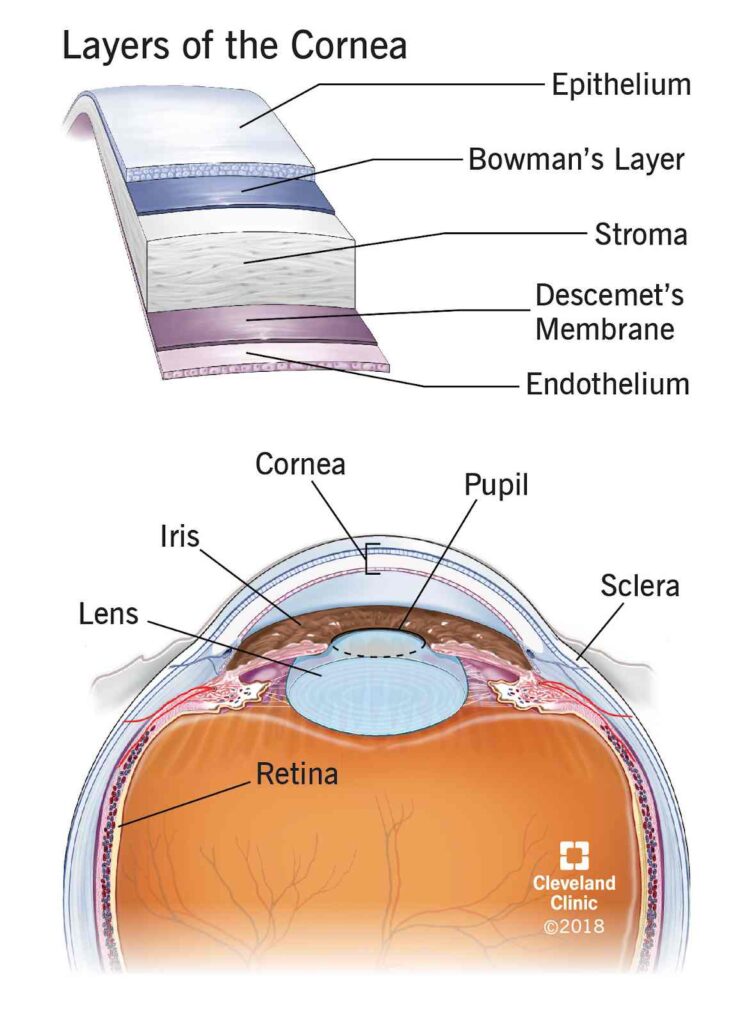

Corneal scarring refers to the formation of fibrous tissue in the cornea, the clear front surface of the eye, following damage to its deeper layers, particularly the stroma. This scarring process involves the deposition of collagen and other matrix components that can disrupt the regular arrangement of collagen fibres, essential for corneal transparency. As a result, corneal scarring leads to varying degrees of opacification, which can significantly impair vision by blocking or scattering light as it passes through the cornea, thus reducing the clarity and focus of the visual image [4][9][10].

Common Causes of Corneal Scarring

Corneal scarring can result from several factors:

- Injuries: Physical trauma such as scratches, punctures, or chemical burns can lead to scarring. Corneal foreign bodies, common in occupational settings, often cause secondary infections or scars if not managed properly [6][13][16].

- Infections: Various infections can lead to corneal scarring. Herpes zoster keratitis, a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus in the ophthalmic nerve, can cause severe inflammation and scarring. Other infectious agents include bacteria, viruses, and fungi, which can lead to conditions like microbial keratitis, often exacerbated by improper use of contact lenses or inadequate treatment [3][7][15].

- Surgeries: Surgical interventions, particularly those involving the cornea or adjacent structures, can inadvertently lead to scarring. Complications from procedures like LASIK or cataract surgery may result in epithelial-stromal defects that contribute to scarring [8][14].

Symptoms and Vision Clarity Impairment

The primary symptom of corneal scarring is a decrease in visual clarity. This manifests as blurred or cloudy vision, depending on the scar’s size, density, and location, particularly if it is situated along the visual axis. Other symptoms may include pain, redness, and sensitivity to light, indicative of ongoing inflammation or infection [5][11].

The disruption of the cornea’s smooth surface and transparency due to scarring directly impedes light from focusing correctly on the retina, leading to distorted or reduced vision. In severe cases, this can significantly affect daily activities and quality of life, necessitating interventions ranging from corrective lenses to surgical procedures like corneal transplants [11][12].

The Limitations of Conventional Solutions

Traditional Treatment Methods and Their Limitations

Corneal Transplant

Corneal transplant, also known as keratoplasty, involves replacing a damaged or diseased cornea with a healthy donor cornea. There are two main types: full-thickness (penetrating keratoplasty) and partial-thickness (lamellar keratoplasty). Despite its effectiveness in restoring vision, corneal transplant comes with several limitations.

One significant challenge is the risk of acute rejection, which can profoundly affect graft survival. Studies have shown that acute rejection (AR) of corneal transplants has no identifiable activation signature within the B cell and T cell repertoire at the time of AR diagnosis, suggesting that peripheral blood genetic or cellular assays are unlikely to be clinically exploitable for prediction or diagnosis of AR [17]. Additionally, the scarcity of donor corneas limits the availability of this treatment option [21].

Laser Surgery

Laser surgery for corneal and other ocular conditions includes procedures like laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS), and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). These methods offer precision and reduced recovery times compared to traditional surgeries.

However, they are not without limitations. For instance, laser surgery can be limited by the anatomical accessibility of the target area, as demonstrated by challenges in delivering laser light to certain locations within the larynx due to line-of-sight limitations [18]. Furthermore, the costs associated with femtosecond laser technology represent a significant disadvantage [19].

Risks, Recovery Time, and Potential for Surgical Complications

Risks and Surgical Complications

Both corneal transplants and laser surgeries carry risks of complications. For corneal transplants, the risk of graft rejection remains a significant concern, with factors such as HLA class II matching influencing the likelihood of rejection [24].

Laser surgeries, while generally safe, can lead to complications such as diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK), a potential sight-threatening condition that can occur even years after the procedure [20].

Additionally, the precision of femtosecond lasers in cataract surgery, while reducing the risk associated with manual techniques, does not eliminate the potential for endothelial cell damage and other ocular structure injuries [23].

Recovery Time

The recovery time varies between corneal transplants and laser surgeries. Corneal transplant patients may experience a longer recovery period, often taking several months to a year for complete visual stabilization [17][21].

In contrast, laser surgeries typically offer quicker visual recovery, with many patients experiencing significant improvements within days to weeks post-operation [22]. However, the recovery process can be influenced by individual patient factors, the specific procedure performed, and the occurrence of any complications.

In summary, while traditional treatment methods like corneal transplants and laser surgeries have significantly advanced the management of corneal and other ocular diseases, they are not without limitations. Understanding these limitations, alongside the risks and potential for surgical complications, is crucial for optimizing patient outcomes and guiding future innovations in ocular surgery.

The Scleral Lens Solution

Introduction to Scleral Lenses as a Safer Alternative

Scleral lenses are increasingly recognized as a safer alternative for managing various ocular surface diseases and corneal irregularities. These lenses are particularly beneficial for patients who cannot tolerate other types of contact lenses or whose conditions cannot be adequately managed with standard eyewear or surgical interventions.

The safety and efficacy of scleral lenses have been well-documented in recent studies, showing significant improvements in visual acuity and quality of life for patients with conditions like keratoconus and severe ocular surface disease [25][26][27][29].

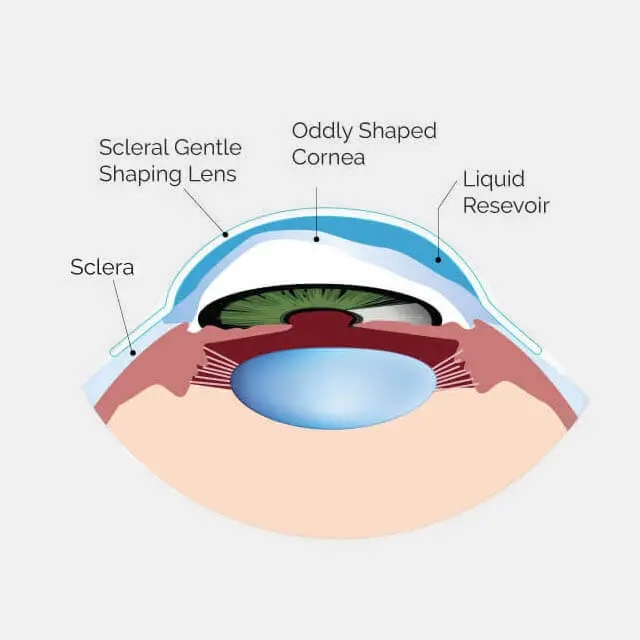

Design and Function of Scleral Lenses

Scleral lenses are designed to vault over the entire corneal surface and rest on the less sensitive white part of the eye, known as the sclera. This unique design allows for a tear-filled chamber to form between the cornea and the lens.

Image source: https://eyecarepaducah.com/scleral-lenses/

This reservoir can hydrate the eye, which is particularly beneficial for patients with dry eye syndrome or those with scarred corneas due to injury or disease. The presence of this tear reservoir helps to protect and heal the ocular surface by providing continuous lubrication and shielding the cornea from the external environment and the mechanical shearing effects of blinking [25][27][28].

Vision Improvement without Surgery

Scleral lenses improve vision by creating a smooth optical surface over irregular corneas, which is often a consequence of conditions like keratoconus or post-surgical complications. This capability allows for the correction of severe astigmatism and irregular astigmatism that standard glasses or soft lenses cannot correct.

The improvement in visual acuity with scleral lenses has been demonstrated in multiple studies, where patients have shown significant visual enhancement without the need for invasive surgical procedures. These lenses offer a non-surgical alternative that can delay or even eliminate the need for corneal transplants in some keratoconus patients [26][27][29][30].

While modern scleral lenses offer numerous benefits, some disadvantages of scleral lenses include the need for proper fitting and care, as improper use can lead to discomfort or complications. However, scleral lens patients who work closely with an eye care professional to obtain a proper scleral lens prescription often experience a successful and comfortable wear experience.

References:

-

[1] Bulut, Mehmet. “Visual Rehabilitation and Tolerability Using Hybrid Contact Lenses of Patients with Moderate to Severe Keratoconus.” (2017). (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/d7978887a9c454c7353e8e641c93a86c5b2033ba)

-

[2] Robaei, Dana, and Stephanie Watson. “Corneal blindness: a global problem.” Clinical & experimental ophthalmology vol. 42,3 (2014): 213-4. doi:10.1111/ceo.12330 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24734984/)

-

[3] Marasini, Sanjay et al. “Managing Corneal Infections: Out with the old, in with the new?.” Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 12,8 1334. 18 Aug. 2023, doi:10.3390/antibiotics12081334 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10451842/)

-

[4] Liu, Li-Rui et al. “Research progress on animal models of corneal epithelial-stromal injury.” International journal of ophthalmology vol. 16,11 1890-1898. 18 Nov. 2023, doi:10.18240/ijo.2023.11.23 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38028511/)

-

[5] Hoque, Kazi Nasimul. “Evaluation Outcomes and Complications of Temporary Suture Tarsorrhaphy (TST) in Cases of Impending Corneal Ulcer Perforation.” Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (2023): n. Pag. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/cf974f36f73722d248701b457f84db0d5f698ab1)

-

[6] Sharma, Samata et al. “Epidemiological pattern of corneal foreign bodies and utilization of protective eye devices: a hospital-based cross-sectional study.” International Journal of Occupational Safety and Health (2023): n. Pag. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/392790fb9ca06d5d4befe9f788da60d2cb78bb8d)

-

[7] Ramatchandirane, Balamurugan et al. “Progression of corneal sub-epithelial infiltrates in a case of undertreated epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.” Latin American Journal of Ophthalmology (2023): n. Pag. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/cdfabc8abd864e18a4b7d20d52314ac1f7d56b8d)

-

[8] Bonte, Anne-Sophie et al. “Severe Corneal Damage After Minor Eyelid Surgery: A Case Series.” Eye & contact lens vol. 50,4 (2024): 194-197. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000001079 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38386977/)

-

[9] Jeon, Kye-Im et al. “Defining the Role of Mitochondrial Fission in Corneal Myofibroblast Differentiation.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science vol. 63,4 (2022): 2. doi:10.1167/iovs.63.4.2 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8994166/)

-

[10] Syed, Zeba A et al. “Corneal Wound Healing in the Presence of Antifibrotic Antibody Targeting Collagen Fibrillogenesis: A Pilot Study.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 24,17 13438. 30 Aug. 2023, doi:10.3390/ijms241713438 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10488077/)

-

[11] Macedo-de-Araújo, Rute J et al. “Improvement of Vision and Ocular Surface Symptoms With a Scleral Lens After Microbial Keratitis.” Eye & contact lens vol. 47,8 (2021): 480-483. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000794 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33928923/)

-

[12] Hong, Merrelynn et al. “Impact of Exposomes on Ocular Surface Diseases.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 24,14 11273. 10 Jul. 2023, doi:10.3390/ijms241411273 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10379833/)

-

[13] Onkar, Abhishek. “Commentary: Tackling the corneal foreign body.” Indian journal of ophthalmology vol. 68,1 (2020): 57-58. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1625_19 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6951207/)

-

[14] Hollick, Emma J. “A fuller picture? National registry studies and the assessment of corneal graft outcomes.” The British journal of ophthalmology vol. 107,1 (2023): 1-2. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2022-321938 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35701078/)

-

[15] C.L, Vasudha et al. “A study on mycological profile of corneal ulcers in a tertiary care hospital.” Indian Journal of Microbiology Research (2019): n. Pag. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/d6bc2ccbde7aab09b5d0c8e404187fb94725332c)

-

[16] Jyoti, agadla. “Rare cases of corneal scar management after ocular trauma with 0.03% flurbiprofen and 0.5% loteprednol etabonate.” (2020). (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/b2b7b805d457b266bfdd194e952e8b4d38f6fa06)

-

[17] Hjortdal, Jesper et al. “Peripheral blood immune cell profiling of acute corneal transplant rejection.” American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons vol. 22,10 (2022): 2337-2347. doi:10.1111/ajt.17119 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9796948/)

-

[18] Chan, Isabelle A et al. “On the Merits of Using Angled Fiber Tips in Office-based Laser Surgery of the Vocal Folds.” Proceedings of SPIE–the International Society for Optical Engineering vol. 11598 (2021): 115981Z. doi:10.1117/12.2580454 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33986560/)

-

[19] Narayan, Akshay et al. “Laser-assisted cataract surgery versus standard ultrasound phacoemulsification cataract surgery.” The Cochrane database of systematic reviews vol. 6,6 CD010735. 23 Jun. 2023, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010735.pub3 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37369549/)

-

[20] Grassmeyer, Justin J et al. “Diffuse Lamellar Keratitis in a Patient Undergoing Collagen Corneal Cross-Linking 18 Years After Laser In Situ Keratomileusis Surgery.” Cornea vol. 40,7 (2021): 917-920. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002653 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34086008/)

-

[21] Ostrovsky, D. S. et al. “Preparation and evaluation of a suspension of human corneal endothelial cells isolated from the eyes of cadaveric donors for transplantation in an ex vivo experiment.” Russian Journal of Transplantology and Artificial Organs (2023): n. Pag. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/f35d92491868327dcb9b9b46df57f0f3dbf62a11)

-

[22] Swaminathan, Uma and Sachin Daigavane. “Comparative Analysis of Visual Outcomes and Complications in Intraocular Collamer Lens, Small-Incision Lenticule Extraction, and Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis Surgeries: A Comprehensive Review.” Cureus (2024): n. pag.(https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/95168dd5aac75624ffa8ea56a7ac0c56c22fa93c)

-

[23] Kecik, Mateusz, and Cedric Schweitzer. “Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery: Update and perspectives.” Frontiers in medicine vol. 10 1131314. 2 Mar. 2023, doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1131314 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10017866/)

-

[24] Armitage, W John et al. “Corneal transplant follow-up study II (CTFS II): a prospective clinical trial to determine the influence of HLA class II matching on corneal transplant rejection: baseline donor and recipient characteristics.” The British journal of ophthalmology vol. 103,1 (2019): 132-136. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311342 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29567793/)

- [25] Shorter, Ellen and Victoria Butcko. “Scleral Lenses in the Management of Ocular Surface Disease.” (2018). (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/73a5833f96e4aaad1bbd56b095bbdb0eebc119ba)

- [26] Kreps, Elke O et al. “Mini-Scleral Lenses Improve Vision-Related Quality of Life in Keratoconus.” Cornea vol. 40,7 (2021): 859-864. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002518 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32947413/)

- [27] Chaudhary, Simmy et al. “Scleral contact lenses for optimal visual recovery in a case of severe acid burn with total lagophthalmos.” BMJ case reports vol. 15,7 e248384. 5 Jul. 2022, doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-248384 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35790322/)

- [28] Porcar, Esteban et al. “Fitting Scleral Lenses Less Than 15 mm in Diameter: A Review of the Literature.” Eye & contact lens vol. 46,2 (2020): 63-69. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000647 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31436759/)

- [29] Fuller, Daniel G, and Yueren Wang. “Safety and Efficacy of Scleral Lenses for Keratoconus.” Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry vol. 97,9 (2020): 741-748. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001578 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7547898/)

- [30] Amorim-de-Sousa, Ana et al. “Multifocal Electroretinogram in Keratoconus Patients without and with Scleral Lenses.” Current eye research vol. 46,11 (2021): 1732-1741. doi:10.1080/02713683.2021.1912781 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33823736/)

This Article is Medically Reviewed by Oh Poh Ling

Poh Ling graduated as an optometrist from SEGi University. She believes that a person will be able to fully enjoy life when they have comfortable vision and healthy eyes. Poh Ling is involved in numerous vision screenings for the underprivileged school children and also for the public in an aim to promote awareness about the importance of regular eye examination. She enjoys travelling and playing tennis.

Her Specialties includes:

1. Specialty contact lens fitting: Keratoconus

2. Orthokeratology

Favourite Quote: “While there’s life, there is hope.” – Stephen Hawking